The following post was written by Gap Year Fellow Jennings Dixon.

Two summers ago I attended a pre-college program at Davidson College where I took two college courses, one of which was called “The Universal Language of Music…Or Not?” In this class, we took the common phrase of “music is a universal language” and attempted to either validate it or debunk it. We studied a myriad of musical traditions from all around the non-Western world, from throat singing in Mongolia, to the didgeridoo in aboriginal Australia, to djembe drumming of West Africa.

Our mission in this three-week course was to break down these musical traditions, identify their basic mechanics of rhythm, melody, and harmony, and then compare them to those of standard Western music. After listening and studying lots of music from around the world, I had personally come to the conclusion that music was not a universal language, but rather a universal phenomenon. What I meant by this was that music had different meanings and different practices in different places worldwide that could not be translated or understood uniformly. The art of music is just too complex to say it was universal.

Now, I have just completed a four-month stint teaching music in Sri Lanka with the nonprofit The Music Project. Our goal was to bring music to low income schools in hopes that the students would find a passion and haven in music. We taught at three schools, helping the students learn how to play instruments and understand the fundamentals of music. During this experience, I constantly thought about the phrase “music is a universal language,” and what I’d concluded after my course at Davidson. This is what I gathered:

Music IS NOT a universal language.

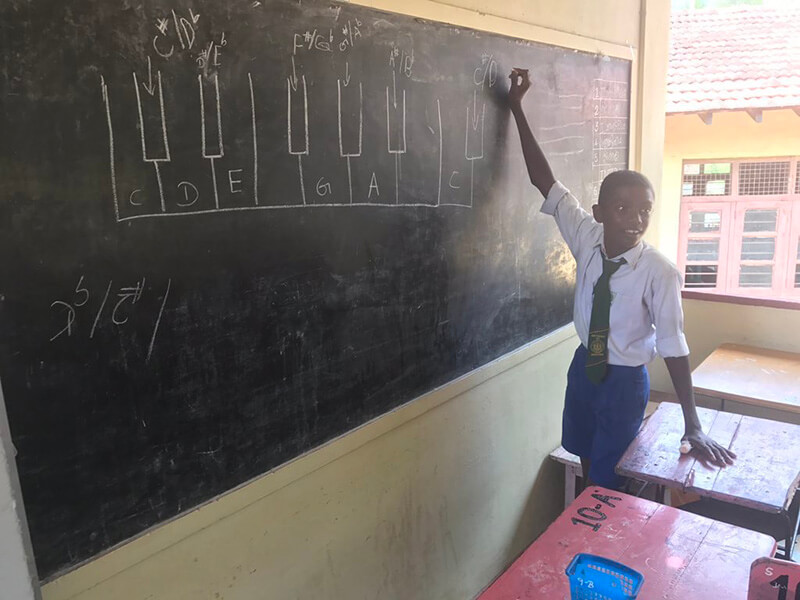

At the Music Project, we taught the students traditional Western orchestral music. The students could choose from a variety of instruments including violin, flute, trumpet, and trombone. Then they’d learn music of the likes of Mozart and Beethoven. I would teach them things such as scales, rhythms, and notes that were musical essentials for Western music. None of those specifics, including the instruments, have been previously found in traditional Sri Lankan music. Everything I taught was of the style that I had learned in school — not the same as theirs. At times, I could tell the students were lost, since the music being taught to them was so foreign and strange. I myself would experience the same effect whenever they would play Sri Lankan music. I couldn’t understand it at first because everything about it was so different from what I had always been exposed to. However, after listening and observing, I understand it better. You just have to learn it.

Music IS a language

Despite all of the very strong factors dissuading me to believe music is a universal language, I do recognize it as a language. Once taught and understood, the world becomes a clearer place. After learning about Sri Lankan music, so many things about the country made sense. I began to understand and better appreciate things like the religion, the culture, and the customs. I felt more connected to the people and places of the country, which I don’t think would’ve been possible without music.

Music also became an actual language for me. The students and staff had limited English ability, and my knowledge of Sinhala was nonexistent. I found that even where words were not an option, music still was. Music very quickly became a bridge that connected us served as a way for us to communicate. Especially with my students, music allowed me to establish understandable conveyances with things such as call and response. I would play something for them and they would play it back. Through this activity, we would be able to operate purely based on us playing for each other. It was genuine dialogue, just through music.

During the four months I spent teaching music in Sri Lanka, I gained a better understanding of what music is. I still don’t think that it’s a universal language. Seeing the students struggling to grasp Western music, and feeling my own struggle with Sri Lankan music, I didn’t necessarily get a sense of universality. With that being said, I also don’t think that music is just simply a “universal phenomenon.” Although it does appear in essentially every culture and civilization in the history of mankind, I think that definition is too simplistic. Instead I believe that music is just a family of many languages. Like English or Sinhala, you grow up hearing and understanding one, and then you can gain the skills to learn another and another. I believe that music is an essential aspect of humanity and human expression, and I think that it is a complex entity waiting to be explored.